he foundation’s treasurer, full of vim and energy, (or prunes as my mother’s friend used to say) assured us that all remodeling would be finished within three months. Well, one and a half years later, M Ludovic was still keeping on keeping on.

he foundation’s treasurer, full of vim and energy, (or prunes as my mother’s friend used to say) assured us that all remodeling would be finished within three months. Well, one and a half years later, M Ludovic was still keeping on keeping on.

We had moved into the big house by then, slowly claiming the four bedrooms plus living and dining rooms from the jaws of oblivion. Meanwhile M Ludovic made fires in the garden (we don’t have yards in France), burning remnants of house from the little house, and, boy, did it stink. Certainly illegal, but a lot easier than ferrying it all off to the dump.

WORKS

Works is how these projects are identified in France. Our works required a deep trench to be dug on the way out the door, obliviating the sidewalk. A couple of times a day M Ludovic would gently lift my daughter up and carry her like the princess she was out the gate and onto the public sidewalk. (A word about gates. Every house had a tall, painted, locked gate. Every door in Paris has a keypad and a code.)

One day we came home from a brief outing and M Ludovic greeted me with a surprise. He’d made a patio for me between the houses, which was the sweetest thing. Unfortunately, though, he had used this awful nubbly material that the treasurer had chosen to remake the sidewalk, which ran alongside the barely-tamed ivy. I had been amassing flagstones out back, intending them for the patio. I never told him. And we loved that patio he made us. Many a summer night underneath the trees as gradually we reclaimed the ur fairy tale house, the one belonging to an ogre or a hidden lost queen.

WORKERS

M Ludovic told me about Apostrophes, a famous French TV program hosted by French personality Bernard Pivot, focused on literary and political figures, ranging from Nabokov to Susan Sontag, and included French intellectuals and filmmakers, such as Roman Polanski, and even the Dalai Lama. M Ludovic knew I was a writer and wanted me to benefit. My French, however, was rudimentary at the time. But I appreciated M Ludovic, a cultivated man and a genius at modernizing two houses, oddly enough on one property.

The cultivated French workman is an idea I believe expressed in Peter Mayle’s book, A Year in Provence. Workman have long talks about wine with their customers, and we shall see that M Ludovic’s specialty was champagne. This expansive understanding of people in all walks of life prevents us from underestimating the two men under a tree in Beckett’s play. Some critics object to calling them tramps or hobos because Beckett never does. But can’t they be tramps and savants? Perhaps they are enduring and endearing because they materialize some aspects of our unsettled selves, where we have been marginalized or suffered abject misery due to one vicissitude or another.

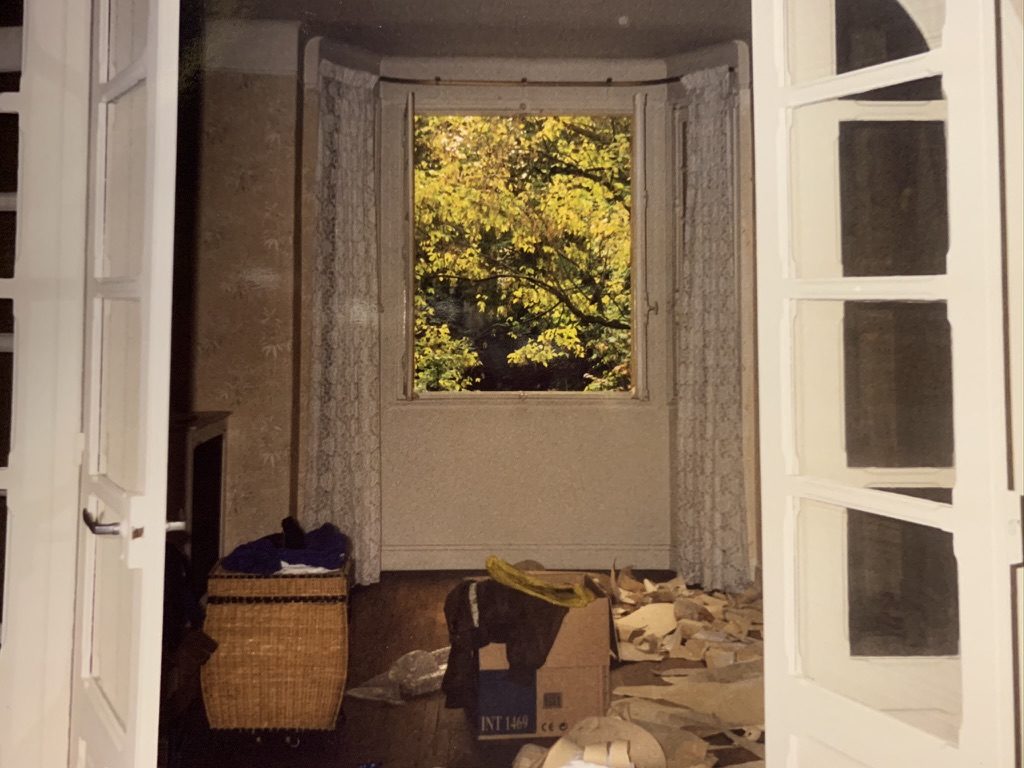

We had beautiful French doors, and a view right through a vacant window! Definitely worth salvaging!

THE HARDWARE STORE

Like Peter Mayle I have my own stories about, for example, needing a level to make sure that my sanded wall was flat.

Soooo, off to the hardware store. Find it, drive down down down the narrowest of passageways in the parking garage, barely wide enough for a skinny French 2 cheveaux, and not really a tomato red Volvo. Down to floor minus one, then floor minus two, three, four and five. Amidst a sea of cars in the vast parking garage, you ask where is the entryway? And thinking ahead, what exit will you take to get out to the street you want? Wrong exit and you will never see home again. Remember your floor. Wrong floor and you will never see your car again. A drive to the hardware store is not for the faint of heart.

Arrival. Phase one in the mission complete.

“Monsieur, “ I say, running after a person in a red coat, a rare specimen, someone who works there. “I need,” and here I pause. What is a level in French? Who knows? Well, it’s like a stick. “A baguette,” I say, which is a stick as well as that famous bread. And there is a bubble in it. Word for bubble? Nope. How about ball? “Balle.” (Un ballon is really better, but who knew?) Une balle is also a bullet. Now here I am, asking for either a ball or a bullet in a stick or in a piece of bread. A bullet in bread? A bullet in a stick? Or did I need a ball in the same bread? Or was that ball in a stick? The man slowed down, stared at me, and shook his head, then gathered speed as he went off to do whatever it is people in hardware stores do instead of waiting on customers.

Come to find out, the word level, such as, what level of French do you speak, is exactly the same word for the tool, “un niveau.” Particularly un niveau à bulle, where bulle is the word for bubble, commonly used, speaking of, for champagne. We talk about the best champagne having, ideally, fines bulles, like in Laurent Perrier, which is to die for! Fines bulles means fine bubbles, not as in, “Hey man, we’ve got us some fine bubbles. No. It’s not fine, as in a fine day. Non. Refined, small. That kind of fine.

THE DUTCH HOUSE

Remodeling features in Anne Patchett’s novel The Dutch House, in which a father and then his son are mad about renovating houses. And while this isn’t the central conflict of the book, it gives us a counterpoint to the way the family’s lives are made and unmade. A brother and sister park outside this house through the years after their mother has left them, only to have the house become the stage for something even more difficult for the siblings. The novel earned the author a nomination for this year’s Pulitzer.

I recently went to hear Anne Patchett speak at the University of Rochester on a fine fall day (not small). The first three hundred guests received a free copy of The Dutch House. I was number 300. Now that says something! (What?)