t was a cold and snowy night in December when I stood at the podium in front of hardy souls at the American Library in Paris about to give a presentation on a novel called in French, La Vie Devant Soi by Romain Gary. The English translation of the title, The Life Before Us, has never satisfied me, but I don’t know how to do better, except maybe Our Life at Hand. This book and author take risks, both playful and serious, and give us an orientation toward literary evaluation which will ultimately be useful in looking at the criticism of Louise Glück in the next couple of posts. Plus, I thought we needed a good laugh this week.

t was a cold and snowy night in December when I stood at the podium in front of hardy souls at the American Library in Paris about to give a presentation on a novel called in French, La Vie Devant Soi by Romain Gary. The English translation of the title, The Life Before Us, has never satisfied me, but I don’t know how to do better, except maybe Our Life at Hand. This book and author take risks, both playful and serious, and give us an orientation toward literary evaluation which will ultimately be useful in looking at the criticism of Louise Glück in the next couple of posts. Plus, I thought we needed a good laugh this week.

Romain Gary had won the coveted Prix Goncourt back in the day, a French prize that can only be received once by an author. And then he was neglected. So, he secretly staged a comeback under the name Emile Ajar by writing La Vie Devant Soi, which became quite the success. It was first published in English as Momo. Under the guise of Gary, the author publicly complained that Ajar was plagiarizing his ideas. How the critics laughed. This jealous, washed up has-been Gary should be so lucky. Emile Ajar was awarded the Prix Goncourt, making Gary the only person to win under two names, and technically twice.

Here is Ajar’s (invented) bio: “Émile Ajar was a 34-year-old Algerian who’d performed a botched abortion on a Parisian while still a medical student. To escape prison – and to explain his absence – he’d had to flee to Brazil, from where he began his literary career. A friend in Rio helped mail the manuscripts, and Gary’s cousin, Paul Pavlowitch, was roped in to play Ajar himself, fielding demands for telephone interviews and photographs.” (Credit in link below)

You might ask what I was doing at the American Library talking about this particular book and this wild Ajar / Gary character. Cornell University, where I graduated as (can you guess) an English major, chose a book each year to be read and discussed by the incoming freshmen and anybody else. So there in Paris, somebody thought it would be fun for Cornellians to join in. I had been the year before to a literary discussion, and to be sociable at that meeting the previous year, I made a comment or two, and by the end I was asked to run the next year’s shebang. Cornell alum, patrons of the library, colleagues from the American School of Paris, my daughter as it happened, were all in attendance on that freezing, slippery-outside December evening.

The story of La Vie Devant Soi is about an aging prostitute, Madame Rosa, who cares for the abandoned children of prostitutes. It is also the story of a young Muslim orphaned boy, Momo, who helps her climb the many flights of stairs up to her apartment, cares for her and finally helps her be comfortable in the basement where she hides her Jewish relics, for she had been in Auschwitz, and where she can die in peace away from the dreaded hospital. I have always thought the author, Jewish himself, took a decided risk in having a Muslim boy help a Jewish woman to die. The only clip I could find in English has the whole movie! But you can get a feel for it in just a few minutes. It appears not to start at the beginning but you can go back once you start the film.

Here’s a critical assessment of Gary (Ajar’s) work: His work involved choices that were not the best, but the best under the circumstances, if you will. Here is an analysis taken from the link below: “He was possessed of a tolerant, humane, grown-up moral vision, and this is what drives his best work – fiction, non-fiction and everything in between. It also makes him the perfect antidote to our polarised, hysterical times, to safe spaces and trigger warnings and no-platform policies.”

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180619-romain-gary-the-greatest-literary-bad-boy-of-all

CONTROVERSY

Let us put our toe back in the water of the Louise Glück controversy. It was an equally snowy night in December when Louise Glück published her acceptance speech. Another parallel I would like to cite is the description of Gary’s vision: I emphasize “tolerant, humane, grown up moral vision,” and am suspect of our “polarized times.” I would like to apply those values to criticism both of her and of her critics. It is quite striking to me how the critics open themselves up to criticism as well. Definitely tune in next week to see how and what. For today, though, I thought we’d start with another acceptance speech of Louise Glück’s to see how she does in that genre of acceptance speeches, and to hear how her name is said (Glick).

RHETORICAL MODES

Besides ethical qualities, I would like to emphasize the rhetorical modes for ways of reaching out to critics as we turn to a critique of Glück’s choices. Before your eyes glaze over, let me quickly say that these “modes” are ways to structure your writing. There are certain techniques, for example, that favor powerful descriptive writing, one of the modes. I am particularly interested in argumentative writing and especially the convention of creating one paragraph of agreement with someone with whom you actually disagree.

REMINDER OF THE PROBLEM

The poet, Louise Glück, whose Nobel Prize acceptance speech was quoted in last week’s blog, began her speech by quoting a late 18th century poem by William Blake, entitled “Little Black Boy.” She also referred to a song used in minstrelsy called “Swanee River.” This poem and song were used to help define her poetic vision which emphasizes the reader as participant. In fact, she created a competition between the two in her grandmother’s attic.

Here is my agreement paragraph with the criticism:

While it is true that Louise Glück was a child of 5 or 6 when she became infatuated with these poems, it is also true that as a mature poet she recurred to these poems without any critical evaluation of her choices. It goes without saying that context changes and develops and without addressing that, Glück falls prey to the criticism of coopting racists tropes whereby a white male poet impersonates a black child in one case, and a white song writer impersonates a lonely black fugitive in the other. Gluck also missed an opportunity to extend her mantle to black poets, those who speak as men and women of color directly to these racist tropes. And yet, despite these failings, her poetry, as opposed to the awkward beginning of her acceptance speech, makes a necessary contribution to our understanding of how literature works.

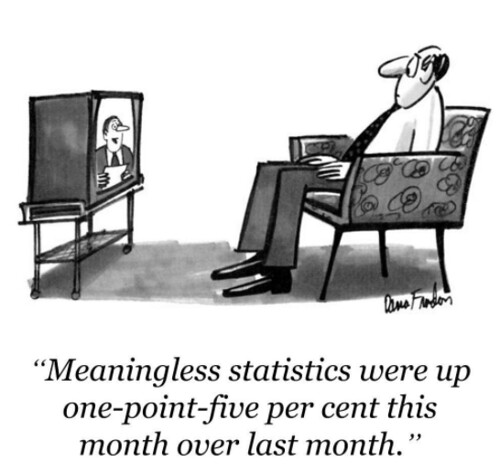

STATISTICAL ANALYSIZS

I wanted to engage everybody in finding some information which will have a bearing on our examination of Louise Glück. Now, I have a friend who is a real statistician and I hope she admires my methodology. Here is our homework. How many American women poets have been awarded the Nobel Prize? You might try googling, but I didn’t get the answers I was seeking. Instead, I had to resort to the sophisticated computation called counting. This link will help you with your statistical analysis. (It has all the names with a little picture next to each winner.) You will see Samuel Beckett in there, and you can wave to him on behalf of Godot.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Nobel_laureates_in_Literature

I am thrilled that the politics of literature is getting the attention it merits. Tune in next week for Poetry and Politics.