ot long ago on the radio I heard a solo piano piece called, I thought, “le Rossignol a disparu.” This means the nightingale has disappeared. Ah, just like Milan Kundera’s nightingale, I thought, who has also disappeared. The nightingale for him is an image of an elusive beauty, which, perhaps, is no longer available to us.

ot long ago on the radio I heard a solo piano piece called, I thought, “le Rossignol a disparu.” This means the nightingale has disappeared. Ah, just like Milan Kundera’s nightingale, I thought, who has also disappeared. The nightingale for him is an image of an elusive beauty, which, perhaps, is no longer available to us.

Now before I tell you about Kundera and his nightingale, and then give you a link to the music, I must tell you something quite interesting: the actual title is Le Rossignol Éperdu by French composer Reynaldo Hahn. Ah, that makes all the difference. Ricky Ricardo would say, “Lucy, you’ve got some ‘splaining to do.” The nightingale, lost for Kundera, is returned to us in a certain way. This is a fitting return given that spring and Easter celebrate return.

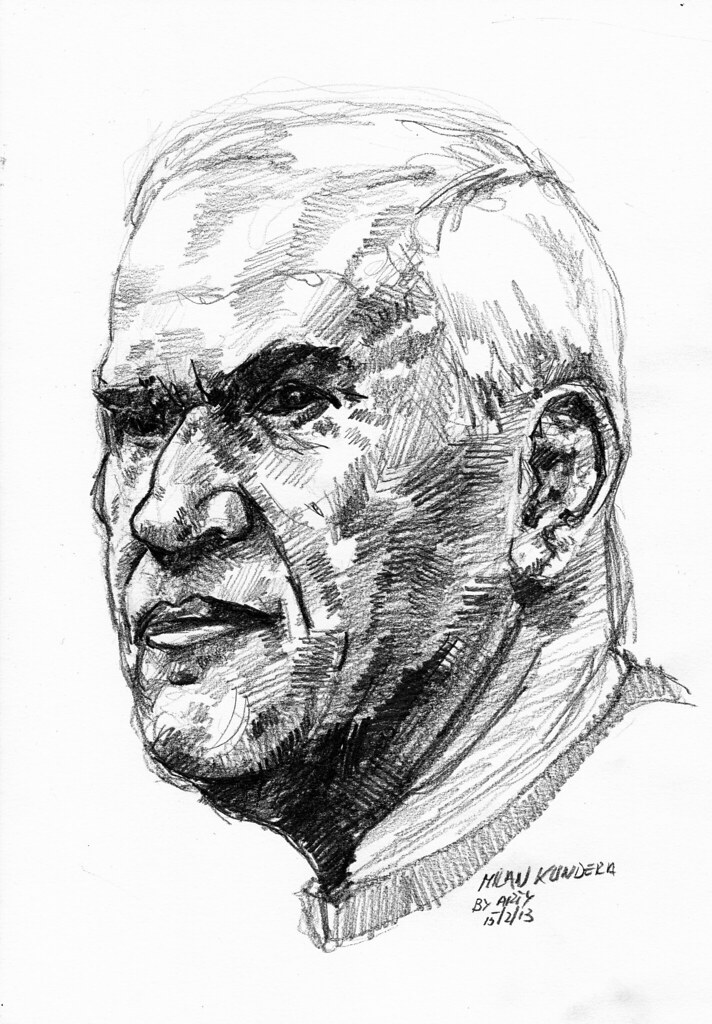

KUNDERA

Milan Kundera, born in the former Czechoslovakia on 1 April, 1929, went into exile in France in 1975 and now identifies as a French writer. He is an influential novelist because of his fascinating discussions on literary history, including the art of the novel. I’d like to explore what he says so that we can appreciate this missing nightingale.

WHAT IS A NOVEL?

In an interview published in the literary magazine Salmagundi in 2014, and translated from the French by Linda Asher, Kundera takes us to the absent nightingale via the history of the novel. He sees the novel as a variety of ways to investigate the self and the possibilities of human existence, which has come to preclude the nightingale.

He expands his definition of the self, borrowing a term from the German philosopher Heidegger, “being in the world.” When the world changes, the self changes. Kundera says that a person is tied to her experience in the world as a snail is tied to its shell.

To illuminate this relationship, when Kundera creates a character, he lists their existential preoccupations, rather than their psychology or sociological standing. In the case of Tereza, for example, her list includes the body, strength, weakness, and vertigo, which is a drunken embrace of weakness. The other characters have different existential dramas. This is how he works out their existence in the novel. The novel did not always address existence in this philosophical way.

THE BRIEFEST HISTORY

Early on in the history of the novel, it is through action that a character distinguishes himself or herself. Then, according to Kundera, we get a more skeptical French writer (Diderot) who shows a character happily and romantically going off to war and ends up with a bullet in his knee and a limp for life. This character would not recognize himself in his actions. “Between the act and himself a fissure opens.” Sound familiar, Dear Reader?

The next step in the development of the novel is interiority, when in the epistolary novel Clarissa thoughts are written down. Who could celebrate the inner life more fully than Proust, the master of lost time? He is followed by Joyce who grapples with the present moment. Kundera writes, “There would seem to be nothing more obvious, more tangible and palpable than the present moment. And yet it escapes us completely. All the sadness of life lies in that fact.”

You might think the history of the novel would stop here, but it doesn’t. The very fact of our inner life is questioned. The famous example of the inner life slipping away is when Kafka’s protagonist awakens as an insect. The character’s inner life would not make any difference in the world in which he finds himself.

NIGHTINGALE

Now that we have seen the progression of how authors situate their characters in the world, we also see what Kundera believes we have lost. Loss fascinates writers: the end of days, the end of time, the end of love. Here’s Kundera: “When a phenomenon proclaims, far in advance, its imminent disappearance, many of us know and perhaps even regret it. But when the agony draws to a close, we are already looking elsewhere. The death becomes invisible. It’s some time now since the river, the nightingale, the paths through the field have disappeared from man’s mind. When nature disappears from the planet tomorrow, who will notice? … There may be nothing so quiet as the end.”

Has the trajectory really gone this far? Have we gone from the human in concert with his or her actions all the way not only to a rupture but a forgetting? For what else can that disappearance signify if not forgetting?

BEAUTY

There is a quiet reference to Keats, whose “Ode to the Nightingale” hovers here in the margin. Has Keats’ nightingale, too, like poetry, disappeared from our mind? It is this disappearance from our inner selves, our mind, that is troubling, even as the threat to nature is occurring. How can the nightingale disappear from our minds? That seems a loss too great to bear. It is not just the nightingale but that deep, ephemeral beauty which has so moved us, is also gone.

I think we can find that beauty again by returning to the actual name of the piece Le Rossignol Éperdu. The word éperdu does not, in fact, mean “lost” in the sense of having disappeared. The etymology of the word suggests that the meaning is to be outside of oneself; to lose oneself totally. In ordinary French it means to be overwhelmed, to be distraught, or to experience something very deeply. To lose oneself may paradoxically be the very rescue that the nightingale, the river and the fields are in need of. By losing itself the bird shows us the way to resurrect that missing beauty. We can lose ourselves in this music as a way of finding ourselves again. Here is the link:

GODOT

Kundera did not touch on the absurd in his passage from action to interiority to the limited world. He might believe that Godot in Beckett’s play, Waiting for Godot, has disappeared, and that the vagrants hopes that Godot will save them is in vain. And with his disappearance, the ability to be saved at all is gone. The vagrants are lost. All is lost. But what if, like the nightingale, Didi and Gogo are not perdu, not lost souls, as we might think of them. What if they are deeply moved by existence, éperdu? In the play, the characters are stripped of striving and purpose. The play itself has no plot and may well qualify as one of Kundera’s examples of a post interior way of telling a story. And yet we are right there with them, éperdu ourselves in that fissure that opens up between what we hear the world to be and how we experience it. The fissure affords the means of losing oneself and yet being deeply moved by losing ourselves in our being in this world.