THE PEOPLE’S CHOICE

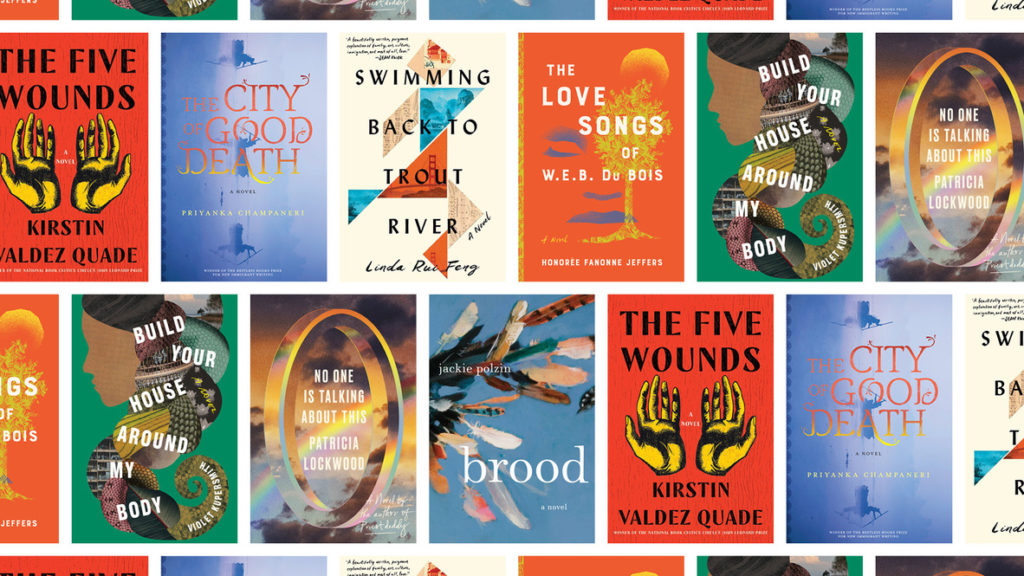

This novel by Violet Kupersmith is the fifth in the series of seven debut novels selected last year by Brooklyn’s Center for Literary Fiction, which later awarded one of the seven a prize. We are putting forward an alternative, The People’s Choice, whereby we read the seven debut novels and choose our own winner. You haven’t (or won’t) read these novels? Not to worry. One previous post of mine extolled the virtues of cheating (within reason), and I invite those readers who have not delved into any of these books to just make your decision based on the comments we present. I’ll put an overview together once we have finished all seven. Just two more novels to go, Brood and The Five Wounds. Readers often come to me with an assessment of a book, which I try to include, and I, of course, provide a brief review myself.

RATIONALE

France is a bookish country as we saw in last week’s post about the French literary season, which happens to be now. So let us become like a French lecture, a reader, and proceed. Even if we didn’t happen to have read the book at hand, I find it interesting to look at the subject matter and the way the book is organized. I hope we become more discerning readers and more discerning citizens, for that matter. Better people. Better men and women. Better quit now.

STORY

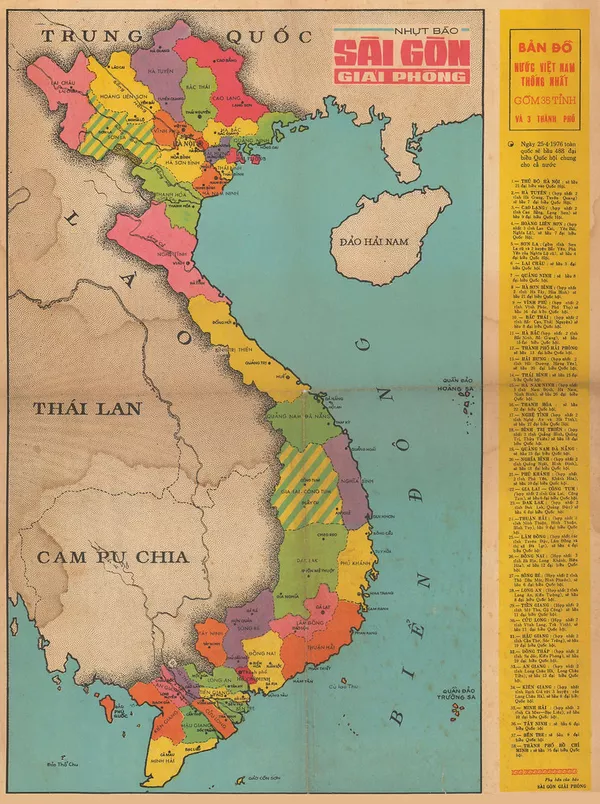

Well, this story is not easy to recap. (Spoiler alerts) We start with Winnie, a Vietnamese / American arriving in Saigon, who goes missing. Her sort of boyfriend begins a desultory search, as the novel, likewise, wanders off in search of Vietnamese history, superstition, murder and intrigue. On the one hand, it is a brilliant collection of various aspects of Vietnamese culture, both present and past. On the other hand, due to its extravagant largesse, it manages to lose Winnie in the process, which is no mean feat because Winnie is already missing!

The chapters are dated with reference to Winnie’s disappearance (one day before; 18 years after, etc.). This way of structuring the novel is a no-holds barred way of paying lip service to a through-line. All manner of unrelated people, ghosts, two headed cobras, dogs and rats come and go, often with no mention at all of Winnie. We are also taken back into French colonial history in Vietnam, first via schoolboys, and then, via French owners of a rubber plantation.

A second woman, Binh, who was murdered, and therefore counts as missing, inhabits a dog and finds Winnie at the end of the novel, teaching Winnie how to leave her own body, which she happily does, becoming first a rat and then a dog herself. Now for sheer fun and playfulness, this is extra as the French would have it, meaning excellent. But what good does this do Winnie? So not only does the scope of the novel lose Winnie, but the end loses her too. The end is especially quirky because in the earlier parts of the novel we see in painstaking realism Winnie’s attempts to adjust to Vietnam, as she tries her hand as a tutor, goes to bars, gets food, is entertained by her brother’s friend, and lives with two annoying American tourists. And by the end of the novel, she has come undone, as has the novel, in my opinion.

MORE RESPONSES TO THE NOVEL

Here’s an American ex-pat’s take on Build Your House Around My Body:

“Another book jumping around in time, but easy to follow thanks to the chapter titles foreshadowing Winnie’s disappearance. I most enjoyed the descriptions of Winnie’s life as an expat, looking native but not speaking or acting native. Not comfortable with locals nor with any of the other teachers. Even despising the earnest habits of an American couple teaching in Saigon, (hiking and juicing) and their sense of superiority. The descriptions of Winnie getting sick and disoriented rang so true. From the start, while we don’t really know why she was there, it was clear she was not well and resigned. ‘She had assumed that one day she would fill all. That her life would provide things worth keeping. That she herself would become someone worthy of being kept.’

“The descriptions of the smoke and transferring bodies gave the story some whimsy. (I didn’t feel fear, just curiosity.) The sense of smell as a dog, the perspective as a rat.

“But I felt like the connections between Winnie, Binh, Tran, etc., were really contrived. Was it necessary to be the same guys? Was the mouth, that Winnie agreed to be, a version of rape and destruction? The revenge didn’t seem to be raw enough.”

Another American says this: “Again, too many twists and turns and back and forth time travel to suit me. I read it over a period of about ten days and I kept losing my way among the characters. I felt like a pinball in a machine, carooming hard off light-up pins, with bells, and in crazy directions!

“I did love some threads, though: the origin of the two-headed snake and the women’s hairs from the trophy book becoming deadly snakes haunting the rubber plantation. One dropped thread bothered me: Susu the Elephant. She lived, she died, was buried and has a Cemetery Monument, but no part in the story. Why is Susu here? (By the way, Koré I am thoroughly enjoying this whole thing.)”

CULTURAL ATTACHE

One aspect of life as an ex-pat is the fascination many of us take in the variety of languages we hear spoken around us in Paris—in the metro, on the street, in the schools. Arabic, Portuguese, eastern European, African, Russian, Serbian, Mandarin, Spanish. Yesterday, in Rochester, NY, when I was getting a manicure, two women spoke back and forth in an Asian language. My manicurist said she was Vietnamese. We got to talking as we do when many coats of polish are applied. She told me she was born in Vietnam. I asked her if French is still spoken there. And she said, no, that it was mainly English. Fifty years ago, yes. And I thought, ah, the end of an era. French colonialism had all the hallmarks of oppression: forced labor, corruption, and “venality,” a word I read used in conjunction with the corrupt administration of Vietnam, a word which seems to add insult to injury in the name of profit. The Michelin tire company recorded thousands of deaths on one plantation alone. Even using the name Vietnam was prohibited. And now that history and even the language are being effaced.

When I taught Social Studies as the American School of Paris, the Vietnam War was part of the curriculum. Since I also taught English, I became a liaison between the two departments, English and Social Studies. The students were tasked with imagining themselves as soldiers, writing letters home. They were graded on content, namely the specifics of the war, by the Social Studies teachers, and then on their reflections, including sensory detail, by the English teachers. A brilliant success? Well, kind of. The students didn’t understand how they could get two differing grades on the same paper. “Well,” I said, “let me tell you.” And tell them I did. Convince them, I did not.

MORE CHEERFUL CULTURAL ATTACHE

It so happens that there is perhaps the largest Vietnamese population outside of Vietnam in L’ile de France, which includes Paris and the surrounding banlieues or suburbs. Vietnamese refugees settled in the Paris region, bringing their food and culture. The Vietnamese now number about 100,000 in the Paris region. The Vietnamese restaurant called Le Palanquin on the rue Princesse in the 6th, for example, is so good that one family visiting Paris ate there every single day during their stay!

WHICH BRINGS ME TO GODOT

A friend wrote that a play where people wait for someone who never comes seems a bit negative. I suppose it is. And yet Beckett calls it a tragi-comedy, suggesting that the experiences of these vagabonds are both tragic and funny. I’d like to say that positivity isn’t enough. I think Beckett took a risk, too, especially for purposes of entertainment, to put forward the play he did. Some people criticized it for being despairing, or too preoccupied with boredom. How do you write a play that includes boredom that is not boring?

Beckett addressed this concern in the play itself. Pozzo, who has arrived with his servant Lucky in tow, (literally) enters into a critique with the two vagabonds:

“Estragon: In the meantime, nothing happens

Pozzo: You find it tedious?

Estragon: Somewhat

Pozzo [to Vladimir]: And you, sir?

Vladimir: I’ve been better entertained.”

I find it both funny and daring to have your own characters unenthusiastic about the play they’re in.

So back to our reviews: remember all this in a couple of months when it’s time to vote. Right?! Meanwhile, read a book! The novel Brood, by Jackie Polzin, is the next one up, to be reviewed mid-October. Send those comments along, s’il vous pláit (if it to you is pleasing). I hope you enjoyed being a French lecture, delving into the culture of Vietnam and looking at a book that was a finalist in an important literary prize.

PS. Notice anything interesting about the plural of suburb? Hint: it’s banlieues. And does anybody know who says this: “Dwell I but in the suburbs of your good pleasure?” Hint: Shakespeare.