his is the third in our series of novels, which, when we have read the seven contestants for the debut novelist prize, we will present the people’s vote.

his is the third in our series of novels, which, when we have read the seven contestants for the debut novelist prize, we will present the people’s vote.

ASIDE

Reader: I am not reading these books.

Me: It doesn’t matter.

Reader: Wait, what?

Me: You may remember that I cheated while playing Go Fish with my daughter, an ethical lapse, perhaps, but necessary to relieve boredom. And it has made my daughter a better person than me.

Reader: Can I remain ethical and cheat in this instance?

Me: Absolutely. Let me explain. Many periodicals present reviews of books, such as NY Times Book Review, and The London Review of Books. If you have a good reviewer, you can learn the essentials of a book, including if you want to read it. Those of you who are only reading my reviews and the comments of others can rank your interest in the books. When it comes time to vote, I’ll repost the reviews.

Reader: What’s in it for me, exactly?

Me: Think sociology, the pulse on our culture.

Reader: That is totally such a great inspiration to read about these books I haven’t read.

Me: Shameless plug for this approach. (See previous sentence.)

NO ONE IS TALKING ABOUT THIS

This book, a novel by Patricia Lockwood, is tricky. First of all, the title. What exactly is no one talking about? To answer this question, let’s look at the story.

THE STORY

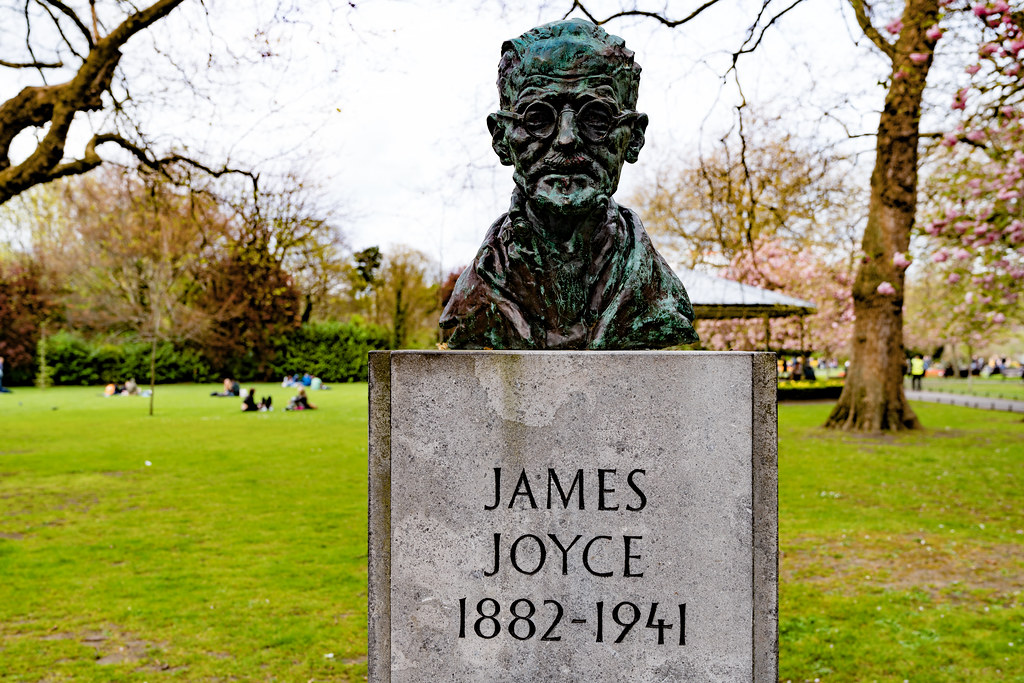

In the course of the novel, the protagonist goes to Dublin where she happens upon a bust of James Joyce and speaks briefly of the inspiration for the book we are reading. She says, “the new book, the communal stream of consciousness began to flow towards the rigid bust of Joyce. … And then because whimsy still belonged to the person, she leaned forward and made a soft pooting sound in the statue’s ear.” This moment reveals the two-part structure of the book. First, the communal consciousness via the Internet, or the portal as it is called here. And secondly, the very personal upending event in her family, which actually happened, when her sister gives birth to a baby with Proteus syndrome, familiar to us from the play The Elephant Man.

Part I, then, features an Internet influencer who goes around the globe, talking about her generation and the portal. Here is an example of a paragraph:

“She had become famous for a post that said simply, Can a dog be twins? That was it. Can a dog be twins? It had recently reached the stage of penetration where teens posted the cry face emoji at her. They were in high school. They were going to remember “Can a dog be twins?” instead of the date of the Treaty of Versailles, which, let’s face it, she didn’t remember either.

You can see the style: short, pithy, absurd, the posts ranging from comments on eavesdropping on sheriffs’ comments to porn stars, forgetting that others could see them, to the way that attention must turn, “like shine on a school of fish, all at once, toward a new person to hate.” She is awash in the particular, random detail, the communal stream of consciousness that is the Internet. Sometimes the narrator personifies voyeurism, as she watches the so called beauty of people being thrown to their death in a carnival ride; sometimes she critiques the experience. “It was a mistake to believe that other people were not living as deeply as you. Besides, you were not even living that deeply.” She slyly puts in posts about Trump, climate change, and the death of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, NC, as well as the shooter in Norway who went on a rampage a few years ago.

Part I is relentless in its particularity, its no-threadness; in its absurdity, its challenges to all of us who are, let’s face it, somewhere on the spectrum of Internet addiction. Happily, there is a genial husband involved who helps ground her. He acts questions such as, “What are you doing?” a question he repeats until his wife looks blankly up at him. “What was she doing? Couldn’t he see her arms all full of the sapphires of the instant? Didn’t he realize that a male feminist had posted a picture of his nipple that day?” In another section, following an episode with a dildo, the husband asks his wife if she is crying. “Of course she was crying. Why wasn’t he crying? Hadn’t he seen the video of a woman with a deformed bee for a pet, and the bee loved her, and then the bee died?” This laughable part about the bee takes on a whole other meaning in Part II.

PART II

Summoned back to the family by her mother, the narrator learns that her sister is carrying a baby with a rare genetic defect, which had been detected in utero. This part of the book is brilliant in a different way. Before she gets this news, and still in Part I, the narrator reflects, “There is still a real life to be lived, there are still real things to be done, she thought one night, helping a friend wash a fine splatter of possum blood off her hands.” One reviewer objects to this kind of writing, where the author can’t let her narrator be serious. In his view, the lack of seriousness paradoxically makes it hard for him to find this kind of writing funny. Do we need the possum’s blood in the same sentence with the real? Is it a tic or a nervousness that the writer feels after all her narrator’s pinwheeling around the portal?

The news of the genetic defect and the decisions that have to be made with regard to this kind of a pregnancy are harrowing. The baby is born and the family, for all its squabbles and political divisions, responds in such a beautiful, empathetic way to the baby, caring for the baby and the mother in such a tender way. The writing keeps its peripatetic pace and sometimes reaches a beautiful sublimity. Speaking of the baby, the narrator says, “Her face was luminous as if someone had put flesh on the bone of the moon, and her beautiful blue eyes were larger than ever, as if coming to the end of what there was to see.” You can tell Lockwood’s early work was in poetry.

The baby lives six months and a day. We witness her death, the choosing of the casket, the funeral.

“Gradually,” as the narrator says, “the world called her back.” She gives a lecture at the British Museum; “Her face was the fresh imprint of her age.” The book ends at a bar with the narrator dancing as someone “slid her phone out of her pocket, and she lifted off her feet, lighter. Her whole self was on it, if anyone wanted. Someone would try to unlock it later, and see the picture of the baby opening her mouth, about to speak, about to say anything.”

So what are people not talking about? Perhaps it’s that the specificity of the Internet doesn’t make it into novels. Or could it be a challenging pregnancy. Other questions: Do the two parts go together? Kind of. Is it immature? Yes. Is it brilliant? Yes. The narrator talks about the thread pulling her back to her phone as if she will find some kind of indestructible coherence. I come away from reading this novel thinking, yes, waiting for Godot.

GODOT

You might wonder what Estragon and Vladimir would make of this idea of the portal. Perhaps they would scratch their heads. Or perhaps they would say of Beckett’s play, Waiting for Godot, that it was a portal of its own. Simpler, perhaps, with a country road, a tree and a moon, and yet with all the some human longings, the same hilarity, immaturity and taste for the absurd.