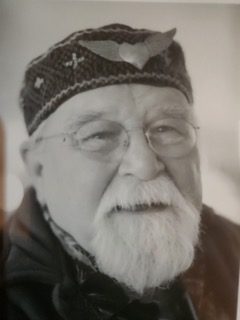

ome of you may have noticed that I refer from time to time to my then-husband, Donald Avery Sharif Graham. I often cite him when people ask me why I moved to France. My then-husband, I will say, was offered an opportunity to work in the archives of the teacher and musician, Hazrat Inayat Khan, who first brought Indian Sufism to the west. An esoteric posting, that is for sure! Without his work there, we would not have moved to France and this blog would not have come into existence. The reason I refer to him fondly today is that he “shuffled off this mortal coil,” in the words of Shakespeare, on 18 February, 2024.

ome of you may have noticed that I refer from time to time to my then-husband, Donald Avery Sharif Graham. I often cite him when people ask me why I moved to France. My then-husband, I will say, was offered an opportunity to work in the archives of the teacher and musician, Hazrat Inayat Khan, who first brought Indian Sufism to the west. An esoteric posting, that is for sure! Without his work there, we would not have moved to France and this blog would not have come into existence. The reason I refer to him fondly today is that he “shuffled off this mortal coil,” in the words of Shakespeare, on 18 February, 2024.

THE LECTURES

Dear Reader, let me start with our time in France, telling you how Don (Sharif as we called him) spent the years from 1998 to 2012.

Inayat Khan gave lectures on music and spirituality around the world. These lectures, happily, were in English and they were stashed under the bed in orange folders of the Dutch woman whose home became Inayat Khan’s archive. Don’s job, as Editor of the Complete Works of Hazrat Inayat Khan, was to put the lectures on the computer chronologically. One other thing: he had to compare any extant documents of each lecture and note any changes from the original lecture. The original lectures, although given, as I say, in English, had been taken down in an esoteric Dutch shorthand. They had to be transcribed back into English, which a colleague did, and then all the versions of every word that diverged from the transcribed shorthand were listed in a footnote. Sometimes there were hundreds of footnotes per lecture.

I was something of a lecture philistine because I could not see the value of a footnote that read, “a” changed to “the” and changed back again. Sharif, however, was a staunch defender. The footnote extravaganza was initiated by two Dutch women whose native language was not English and I imagine they were tentative about articles. My view was to let an English speaker have at it and only list the differences that made a difference.

LOCAL COLOR

These archives were run by a Dutch foundation, who, by definition, were, unfortunately, not American. (They felt the same way about us, that we, unfortunately, were not Dutch.) The archives were located on a one-way French street called Rue de la Tuilerie, a street peopled by English speakers involved in some fashion with the legacy of Inayat Khan, his family, his projects, his vision, his history and his musical passion. Inayat Khan’s son, Pir Vilayat, was a particular friend of Sharif’s. Indian musical evenings, lectures on Plotinus’ theory of beauty, together with lovely meditations on the elements from nature, along with complicated Buddhist breathing practices, enriched our days. “In the suburbs of our pleasure,” (another phrase from Shakespeare, whom Sharif adored), we had the thrill of France: the savor of fresh food and exquisite croissants; the musicality of the language; and for Sharif, the proximity of India, where, before he died, he had visited a dozen times.

ORIGINS

Don came from pioneer stock. His grandfather was 72-years old when his mother was born. So his family history has a great span. His great-grandfather was an ophthalmologist from Germany who made his life in Montana. There, he operated on the eyes of the son of Red Cloud, the leader of the Oglala Lakota from the end of the Civil War in 1865 to 1909. Two warriors stood outside the good doctor’s home, arms crossed, waiting for the boy to heal, which he did. (Would anybody have lived to tell the tale had the offspring of such an important personage failed to recover?) Don’s great uncle gave the name to Pasadena, where he himself was born. Somehow, some of his relatives wound up as travelers with the infamous Donner Party. A cursory glance at Google will tell you that these people, who are sometimes referred to as the Donner-Reed party, were a group of pioneers who travelled by wagon train from the Midwest to California in 1846-47. Those who write for Google with delicate sensibilities are a bit squeamish and out of delicacy omit the terrible snows, the deaths and the cannibalism that ensued.

Don grew up in Prescott, AZ, with his older brother, Lewie, then spent some time in Chicago with his family before graduating high school in the Amphi school district. Off he went to Yale. Upon graduation, with a degree in English Literature, he returned to Tucson, where he taught English and Comparative Religion at the University of Arizona and Pima College.

All three of his daughters were born in Tucson. He was likewise devoted to both of his parents, who also lived in Tucson, attending to them in their older age.

MY FAVORITE STORY

Sharif identified as a story-teller, which many of us thoroughly enjoyed, especially for the first few tellings of the same story. One story I never tired of hearing had to do with experiments he conducted on Kitt Peak, the National Observatory located outside of Tucson. This took place either the summer before or the summer after his first year at Yale, when he was considering being an astrophysicist. The lead scientist was studying the chromosphere of the sun, which for those of us who don’t know, is one of the layers of the sun’s atmosphere. Sharif was asked to read out what is called Fraunhofer lines from the computer. (I can only imagine what those computers were like in the day!) Fraunhofer lines are dark lines in the sun’s spectrum that can be correlated with various elements present in the chromosphere. Clearly explained here, by a lady with an accent, so she must be smart!

Somehow the lead scientist had figured out how to get data from the sun’s chromosphere concerning the elements found there and have them print out on a computer. Imagine Sharif, looking at a ticker tape of lines, and seeing that heavy metals are represented in the sun’s chromosphere, such as iron. He was certain he’d made a mistake. When he took his results to the lead scientist, the man said, “Do you realize that you are the first person on planet earth to know that there are heavy metals in the chromosphere of the sun?”

MY SECOND FAVORITE STORY

Sharif’s passing was very peaceful. He’d toured India for the last time, for a month, visiting the Bodhi tree for the first time, despite his many trips, where the Buddha sat and received enlightenment. When he came home he didn’t feel well, as he often didn’t after long travel. He told a handyman he was at death’s door and then a few hours later, he lay down to take a nap in his recliner and passed away in his sleep.

GODOT

Somehow, after Sharif’s passing, I was drawn to a book called Japanese Death Poems, Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death.

ASIDE

ME: Don’t laugh.

READER: Are you all right?

ME: I didn’t write the thing.

READER: Are you sure?

ME: Ha ha.

This book is surprisingly refreshing, considering its subject matter. Surely Beckett was familiar with this material. So much of his play, Waiting for Godot, seems to be saying that from when we are born we are on the verge of dying. Perhaps we don’t cotton on to that right away, though, fortunately. But characters nudge us in that direction, and sometimes in surprising ways. Estragon says to Pozzo, the man holding Lucky as a slave—he says of Vladimir, “Everything seems black to him today.” And that blackness is limitation and suffering and being in a bad mood and where’s Godot? And Pozzo answers, “except the firmament.” I’m, like, what? The firmament? A cosmic moment in despair. That’s what my haiku book does as well.

Here’s a haiku from Gazen, who died in 1825 at the age of 82, an age Sharif had almost attained but for five days.

“I lean against

the stove and lo!

eternity.”

I love the surprise of eternity. You’re warming yourself or lying down, and voilà.

The commentator writes that “Gazen’s 82 years must have taught him that the world of the senses and the realm of the absolute are found wherever one sees them.” I imagine this is similar to Sharif, who might say, in his version of discovering the firmament,

“I lean against

the recliner and lo!

eternity.”

Bon voyage, Sharif, then-husband, in this new venture.

What a wonderful tribute ❤️ to a wonder-full man, written by his wonderful then-wife.