ne of the joys of being an expat living in another country is that once you come across something, such as an architect of the Centre Pompidou, that something becomes like a stone thrown in a pond, creating ripples that give out ever widening circles.

ne of the joys of being an expat living in another country is that once you come across something, such as an architect of the Centre Pompidou, that something becomes like a stone thrown in a pond, creating ripples that give out ever widening circles.

First, speaking of the Centre Pompidou, I recently wrote that, sadly, it will close for renovation. However, one of our alert readers told me that there had been a reprieve. It will stay open until after the Olympics, which will be held in Paris in 2024 from July 26 through August 11. Work rarely happens in August in Paris, and I imagine everybody will be sighing that sigh of relief when the Olympics are said and done, so, dear Reader, we have time!

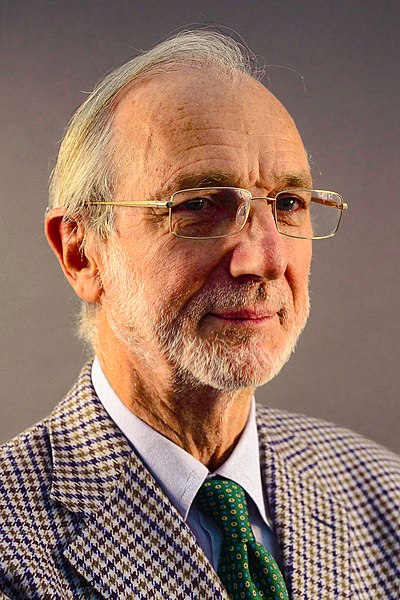

RENZO PIANO

Perhaps a potted biography?

Renzo Piano was born in 1937 in Genoa, Italy, into a family of builders. His first building was a factory in Genoa, using the family know-how to create light-weight materials. His first internationally commissioned building was in Osaka, which was greatly admired and led to his collaboration with Anglo-Italian Richard Rogers, and voilà! Le Centre Pompidou. The man is 85, won the Pritzker Prize, and is renowned not only for the Centre Pompidou but also for the Shard in England and a very cool recent building in Spain, among other museums in the US and buildings elsewhere. Fun facts: He is an Italian Senator for life, and he designed ships.

The Shard in London

Spain

Me: What does not often get mentioned is the Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé Building, located in Paris.

Reader: I have never heard of it.

Me: Exactly.

THE PATHE BUILDING

Perhaps this little sign is familiar to you? It’s a film studio.

The following elaboration is courtesy of our right-hand man, Google.

“The Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé is an organisation dedicated to the preservation of Pathé’s heritage, and to the promotion of cinematography.

“The project called for the demolition of the two existing buildings. The facade on the avenue des Gobelins has been restored and preserved, for its historic and artistic value. Decorated with sculptures by a young Auguste Rodin, it is not only a historical landmark, but also an iconic building for the Gobelins area.

Façade of the Pathé Building

Behind Auguste Rodin’s façade, Piano has erected a five-floor shell-like structure, covered by 7,000 protective shutters. Standing in the middle of a garden, this contemporary building is a virtuoso display of the use of materials. In addition to the glass work on the two upper floors, the interior offers a subtle combination of wood and steel, making this a unique construction.”

MORE ON THE THEATRE AND RODIN

“The Théâtre des Gobelins was built in 1869 by the architect Alphonse Cusin, and was a cultural center for the 13th arrondissement. Its façade, by Auguste Rodin, is classified as an historical monument. It has two sculpted figures on it; a man to represent Drama and a woman to represent Comedy. The theater was later turned into the Gaumont Gobelins-Rodin cinema, but this closed its doors in 2003. They have now reopened to reveal a space dedicated to the history of cinema.”

The reason that I am going to all this trouble with presenting the Pathé building is hinted at in the description of the place as a “shell-like structure.” When you are in there it is the most delicate of feelings, so unlike the Pompidou. That’s a real tribute, in my mind, to an architect or a person, for that matter, to have such a range at his or her command. This is like a hidden gem, which, if you get the chance, is very worth a visit.

Inside the Pathé Building

A NOTE ABOUT GENOA

I had a relative who lived there, the cousin of my grandfather, so you can imagine she was not very young. My husband at the time and I were travelling to Italy and in fact had to change trains in Genoa, so I got the address of Ida Lombardazzi from my aunt, my grandfather’s daughter. A friend who spoke Italian called her and tell her we were coming to Genoa. Off we went to pay her a visit. I assured my husband, who wanted to stash our luggage at the station, that we could just bring our suitcases along because my family was so hospitable. Italians, you know! We would be invited to stay the night. To meet a relative of my grandfather, who died just after I was born, was very exciting.

We arrived, suitcases and flowers in hand. No answer at the door, and yet I thought I saw activity inside. We went to a nearby café, where the owner went off in search of his son, who spoke English. The son went over to her house and said these nice Americans wanted to say hi. It did not go well. The son came back and reported that she jumped a mile when he rang the doorbell. And no way would she even open the door to us because it was obvious we wanted to move in! She even had a son herself, a doctor, who would be my cousin-in-law or something, whom I tried to call, but I only got a busy signal.

Well, a few folks from the café went back with the owner’s son, this time taking the flowers. The townspeople cheered for us, lobbied for her to say hello at least, but to no avail. So my husband and I reluctantly went back to the train station, without having seen her.

Ida later called my aunt to say how sorry she was. “Crocodile tears,” my aunt told me.

Port City of Genoa

GODOT

Beckett was not an architect, nobody lived in Genoa, neither he nor his wife Suzanne, nor the vagabonds, from what we can tell. But there is a prominent architectural feature in the play, the Eiffel Tower. “Named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel … and locally nicknamed “La dame de fer” (The iron lady), it was constructed from 1887 to 1889 as the centerpiece of the 1889 World’s Fair” (Wikip).

At the beginning of the play, Waiting for Godot, Vladimir asks, “what’s the good of losing heart now, that’s what I say. We should have thought of it a million years ago, in the nineties.” Estragon interrupts him, but he continues, referencing the Eiffel Tower. “Hand in hand from the top of the Eiffel Tower, among the first. We were respectable in those days. Now it’s too late. They wouldn’t even let us up.”

So there is a hint of a past with these two. Standing at the top of the Eiffel Tower. “Among the first.” Here was some actual distinction. And then the slide, from respectability, yes, to disrepair, which is what has led to criticism of Beckett for his celebration of despair. But we also see slyly, subtly, a slide away from nonsense, where Godot comes to represent all the desires of this world, the foolish and the noble. These are the two poles that shimmer in the play, the fall from respectability and the fall from nonsense. And the Eiffel Tower as wheel of fortune, where sometimes we’re at the height of good fortune, for no reason of our own, and sometimes we are not at the height. Perhaps Senator Piano could help address these inequalities.

Piano also designed the modern wing of the Chicago Art Institute. A form follows function marvel of a building.

I look forward to visiting. There’s a Camille Claudel exhibit too, I understand, in Chicago.

I didn’t know she was Rodin’s student / mistress and a brilliant sculptor.