hen we use the term “haute couture,” we think of fashion. But something else goes by that name. Would you believe it’s the tea shop in downtown Paris? Mariage Frères offers what reviewers call haute couture du thé. High fashion tea.

hen we use the term “haute couture,” we think of fashion. But something else goes by that name. Would you believe it’s the tea shop in downtown Paris? Mariage Frères offers what reviewers call haute couture du thé. High fashion tea.

On a recent trip to Paris, I felt that familiar thrill of stepping back into the old world of tea trade at 30 rue de Bourg-Tibourg in the Marais, the 4th arrondissement. Even the street name has the word “tea” in it, given that the “i” in French is pronounced like an “ee,” making that “Ti” syllable sound just like our word “tea.” This coincidence will go over a French person’s head because the word for tea in French is pronounced like the first syllable in the word “ta-ken.”

Reader: Marriage Brothers? Do I have that right?

Me: Somebody posed that exact question to professor Google, and here’s what they said: “Mariage Frères, which means the Mariage Brothers, was founded in 1854 by brothers Henri and Edouard Mariage in Paris. They are credited with being the first to create the unique French blended teas, inspired by France’s culinary and wine traditions.”

Reader: Doesn’t the word mariage in French, though, mean marriage?

Me: Yup. A business marriage, you might say, of the Mariage brothers.

So tea. Just like fashion, it is a world. To appreciate it, you have to wean yourself off of boxed tea, the kind that you buy in the store. Turn to a tea shop, to this particular Mariage Frères, when you’re in Paris. And then you buy something called thé en vrac. This is the term for loose tea. And look at the possibilities!

WHY DO THIS?

First, you get to have paraphernalia. For those of us ex-smokers, and those who don’t vape or do drugs of any kind, there is a ritual aspect to preparing a cup of tea. Think of yourself as a chemist. You have to have the right tea strainer. Some prefer a mesh basket. I have an open strainer. True aficionados turn up their noses at tea balls. The leaves are too compressed.

Second, the flavor is so good, I cannot tell you. The hot water swirls around those leaves, the amount of which you can adjust to your taste.

Third, the blends are imaginative and delicious. I used to be a fan of Plein Lune. Full Moon tea.

Here is how it is described: “A warming black tea with delicate honeyed notes and aromas of almonds and sweet spices.” Then, recently, I had Thé de lune. Moon tea. Here it is: “inspired by night under a full moon in a tea plantation. This incense exudes an intense perfume of nature both fresh and sugary, dominated by an amber note.” (What does this even mean?) I think the writers forgot that they were talking about tea and pretended it was wine. But for some, it is wine! Elixir for the soul. And, believe it or not, these two teas with quite similar names have distinct flavors.

TEA

Started in China. Some say an emperor was sitting outside, drinking hot water, and some leaves fell in his cup. He was pleased. Physical evidence of tea from an emperor’s tomb demonstrates that tea was consumed in the second century BC, although Chinese records suggest tea was present as early as 10,000 BC. The modern word for tea in Chinese appears relatively recently (8th century AD), which muddies the proverbial waters. Terms such as “bitter vegetable” in ancient records may actually refer to tea. First medicinal and then as a stimulant, and finally as a highly valuable and expensive commodity, tea has travelled the world. Tea was even used as legal tender.

DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY

While tea was introduced into Japan by Buddhist monks from China, and presumably in mindful tea ceremonies, in Europe it was introduced by the Dutch East India Company. Ah, capitalism. Considered to be the first corporate enterprise, and one of the earliest monopolies, its power rivaled that of any company, to the extent that it had its own militia and minted its own money.

Same with tea in India. The British wanted to circumvent the Chinese monopoly.

ASIDE

I taught at an International School, where students take many of their courses in French, and then enroll in English literature and history and geography. As part of our teaching contract, we were tasked with taking the students on a yearly trip. The offerings included Scotland, Ireland, Chicago and London. I drew the London straw. Part of our tour included visiting Greenwich, where Greenwich Mean Time is established.

The nearby British Maritime Museum, which promised to be filled with moldering old ship data, so I thought, was anything but. The Dutch East India Company was displayed in all its raw, aggressive power. Imagine if Amazon had its own militia and its own money. And told the government what to do! (Well, ok, that we can imagine.)

British Maritime Museum

BACK TO TEA AND MAYHEM

George III approached China in 1793, requesting trade agreements. The emperor responded thusly, “Our Celestial Empire possesses all things in prolific abundance and lacks no product within its borders. There is therefore no need to import manufactures of outside barbarians in exchange for our own produce.” The matter was settled. Well, no because for some reason tea had to be paid for in silver bullion, and to buy all this tea, Britain was losing too much silver, “causing damage to Britain’s wealth.” What is a poor colonial power to do? Britain began exporting opium from regions of British India, which included modern day Pakistan and Afghanistan, and bringing it into China. And while importation increased five-fold, the Qing government cracked down on it because of the societal problems it caused. This was not satisfactory. According to historian Wikipedia, “Tea had become an important source of tax revenue for the British Empire, and the banning of the opium trade and thus the creation of funding issues for tea importers was one of the main causes of the First Opium War.”

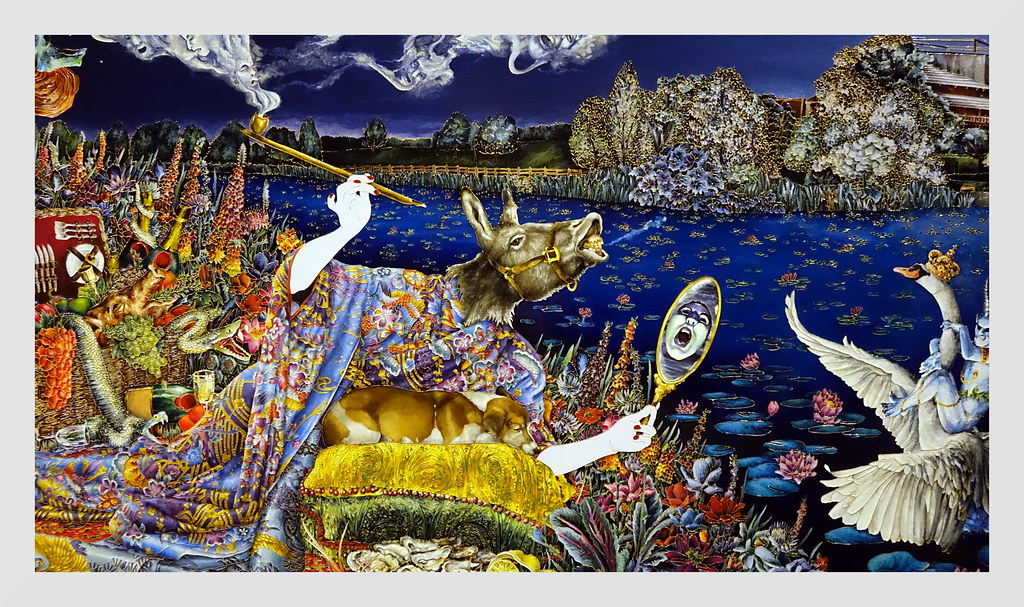

Self-portrait of an opium smoker (Shaw)

THE MAYHEM GOES ON

In the history of tea on Wikipedia we learn that, “While waging war on China was one of Britain’s tactics, it also began to use India for growing tea. After tea plants were smuggled out of China, plantations were established in areas such as Darjeeling, Assam, and Ceylon.[ As an attempt to circumvent its dependence on Chinese tea, the East India Company sent Scottish botanist Robert Fortune to China to purchase and bring out of China tea plants, which were then taken to India.”

GODOT

Samuel Beckett most likely consumed Barry’s Irish tea, the sole exception to the edict forbidding boxed teabags. Barry’s is delicious. Even the most dedicated admirers of Beckett’s play, Waiting for Godot, are hard pressed to find any tea-like ideas in the play. Even the arrangement of tea leaves as a way to predict the future would be welcome. “When will Godot come?” Answer: “Let us arrange the tea leaves.” But alas, none. I am reminded of an election slogan with a Godian slant in the face of not being able to talk about tea in the play. “Yes, we can’t.”

And what does that all boil down to…In the UK the most often consumed tea is probably builders tea. A bag, a splash of milk and your trousers worn 3 inches too low. Not a pretty sight…