EOPLE’S CHOICE

EOPLE’S CHOICE

For those of you new to this project, every month or so we read one of the seven novels nominated for the debut novel prize by The Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. We will then select our own winner (and in the spirit of a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, you can just read the reviews and vote). Here is number four, The Love Songs of W. E. B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers. We have read so far Swimming Back to Trout River, The City of Good Death, and No One is Talking About This.

W. E. B. DU BOIS

Who was W. E. B. Du Bois? First, to pronounce his name. Du Bois rhymes with “Du Choice.”

A Black American thinker and sociologist, W. E. B. Du Bois influenced the debate about the best way to combat racism. Other thinkers of the day, such as Booker T. Washington, believed that Black people should accept segregation temporarily and, in turn, advance in vocational studies. Du Bois argued for protest and activism. He was among the founders of the National Advancement for Colored People, the NAACP, contributing to their monthly magazine called Crisis, which at one point had 100, 000 subscribers. His book, The Souls of Black Folk is a rousing highly acclaimed empirical study of the lives of Blacks, including poetry, memoir and history.

P.S. He also wrote fiction! The Quest of the Silver Fleece, Dark Princess: A Romance and The Black Flame Trilogy.

Choose your video:

For kids (tells about his parents)

For the serious among us

AND THE NAACP?

This is a civil rights organization active today, which is dedicated to social justice for Blacks.

Here is a link to their website.

https://naacp.org/join-naacp/become-member

NOW THE NOVEL

For those of you who have read it, you don’t envy me here! How to describe this novel? It begins like the book of Genesis. Let’s start with Eliza Two Pinchard Freeman, also called Meema. “She will marry a man named Red Benjamin, and he will take her last name. And Meema will bear a daughter named Sheba, who will grow up to be free with her love. And Sheba will bear Clyde, a son … And Red Freeman will pass away.” Already you see you have to keep up as a reader. We see that Red Benjamin took Eliza’s name, but we don’t really register it is as Red Freeman. And when we see that he passed away, the benighted among us will be saying, “Who’s Red Freeman?”

For some that is the bedevilment of this novel. Keeping track of the many generations requires study, especially since there are so many names that change for one reason or another. For others, this epic saga opens up the reader’s mind to a world minutely imagined, depicting generations of a Black family. In addition to that, we have an interwoven “real time” story, focusing on Ailey: her own family life, her coming of age, her love affairs, her family complications, her deep love for her troubled sister. Some readers love this thread that traces one individual through the fabric of the novel against the background of a welter of ancestors. Other readers find the sum total of the ancestors and Ailey at 788 pages too overwhelming (and too long). The threads do come together so beautifully when Ailey both attends and works for a historically black college where her uncle teaches. Through her job as a historical researcher, she finds a family connection in her real time to the ancestors we have gamely been trying to keep track of.

For me, the most powerful aspect of the book has to do with the portrait of one of the most searing experiences we can possibly imagine, which is child sexual abuse. Both in the story of the ancestors, girls victimized by a white slaveholder, and in the real time story, girls victimized by a grandfather, this struggle against pedophilia is such a heartbreaking burden. Ailey’s continued struggle with her past as it plays out in her sexual relationships is brilliantly rendered. Likewise, her sister Lydia’s demise due to drugs is painful to witness.

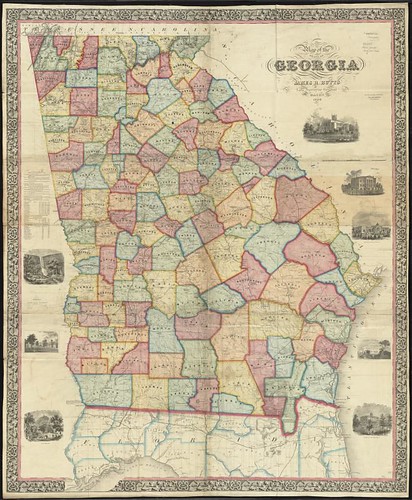

HISTORY

Another strand that’s woven through is that of history. A certain spot in the South was taken over by the whites. And here is how that is portrayed: “The intruders on the land weren’t Englishmen or Scotsmen anymore because a revolution had been fought. Now they were “Americans,” “white” men, and though to the Creek the color white meant peace, that word meant something else to the intruders.” And then follows a progression of re-naming. “And now those called Coromantee or Igbo or Wolof or Fula were ‘Negroes’ or ‘slaves.’ And now the Creek were ‘Indians.’” Three treaties are then named, until we arrive at “The Treaty of Washington in 1805, and our land was no longer what the people called it. Now the white men called us ‘Georgia.’”

We also have paeans to Africa and its loss. And, of course, we have the quotes from W. E. B. Du Bois, serving as commentary.

Actual historical events, such as “The Weeping Time,” in Georgia, where over 400 slaves were sold and the skies poured down rain for two days, are woven into the narrative.

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/07/the-weeping-time/374159/

TECHNIQUE

This is circular story-telling, where Ailey, the focus of the real-time story, says what it’s like when her sister Lydia comes home trying to get clean. And Lydia tells the same story. That happens with Ailey’s mother, whose marriage Ailey recounts, and also the mother tells her story. The story moves back and forth between the ancestors and Ailey’s story. History is braided in, as is the celebration of the women both before Georgia became Georgia and after.

FINAL THOUGHTS

One reviewer called the reading of the book like climbing a mountain. But the view from the top is sublime. Another said it was good material but poorly edited. I agree 100 percent with both!

Here is what our readers say:

One reviewer says this: “I had trouble keeping the characters and experiences straight because of the author jumping forward and backward in time, almost hopscotching, a foot in 2 or 3 worlds at once. What happened to who? When? Where? … Finally, I just gave up and let the various vignettes wash over me, disjointed and scrambled, rather like the bits of my own family’s history as I heard it, first from this one, then from that; all messy, with pieces missing.

“The summing up at the end was helpful but somehow unsatisfying; whole generations skipped, left out of the story. So much time was spent on Lydia, but then “POOF”, she’s gone. The only two male characters I could keep clear in my head were Uncle Root and Samuel Pinchard. All the others were just shadows. I kept thinking of Alex Hailey’s ‘Roots” and how much more clearly that family saga unwound. I learned a bit about drugs and sororities. I liked the EARTH starting the narrative and wish the EARTH had chimed in more often.”

A second reader writes this: “First, I had never heard of W. E. B. Du Bois (Am I just too white? Idaho Klan educated?) so, of course, as usual, I have a whole new list of books to read. The quotes were striking to me not only for their words but also that the same holds true today. It’s so complicated and never ending. The title made me curious, then each quote made me want to go further. The book then illustrates the “songs” in a terrible but sometimes funny way (cf. scrutiny at the airport, “if it’s random, why am I always the one searched? … Do terrorists wear horn-rimmed glasses and carry bags of potato chips and trashy gossip magazines? … Let him go straight to hell with gasoline drawers on”.) So many themes reek of the insurmountable burdens people carry made it tough to read (incest, pedophilia, crack). I had to stop at times. But somehow there is also a message of hope.

“The language or rhythm of the dialogue is incredible throughout the book. I could hear the voices. I would like to have the words/education to describe the author’s ability to slow down and create a melody in parts, but then move back to a more contemporary clip in the more recent sections. Reading over and over again about the plates of fried chicken, sweet potato pie, biscuits and greens made me crave it too! I liked how food was a comfort.

“I heard you say you thought it dragged a bit. But as I was stopping and starting, it was kind of a good thing to hold on to the story longer. Not a short sting of a slap in the face, but a long slow pain that I won’t easily forget, after the last page. I loved the idea of weaving in the past and present, the hierarchies of blacks, Indians, and those who thought they were white. I think it really helped better understand the different perspectives. I really felt the helplessness, the lack of options. It’s a wonder so many people carried on. (Thinking of Toni Morrison’s Beloved.)”

Here’s an interview with the author

GODOT

General agreement among characters and author: America is a mess, still trying to sort out these race relations. Remember that Lucky and Pozzo were involved in a master/slave relationship, a reversible one had the stars been aligned differently at birth. I have always been intrigued that this master / slave arrangement is the one Beckett chose to explore in his play, Waiting for Godot.

A recent victory in LA is that part of Manhattan Beach, called Bruce’s Beach and intended for African Americans, was recently restored to black descendants from whom it had been taken. Is hoping for social justice too much like waiting for Godot? I can only hope not, that Bruce’s Beach will be a harbinger of the collective future over here.