ne day, before school correspondence between teacher and parent had gone on-line, my daughter came home with un mot from her teacher, a word written in what is called le

ne day, before school correspondence between teacher and parent had gone on-line, my daughter came home with un mot from her teacher, a word written in what is called le

carnet. Now le carnet is a most important notebook which documents the student’s existence at the school. And un mot from the teacher could be an announcement of a school trip or her planned absence, or something specific to that student. Before I tell you what this particular un mot was, I wanted to reflect on some words in French. First of all, un mot, a word.

UN MOT

First of all, it is very unlikely that a teacher sent home a word. If she were to send home one word to describe my child, what would it be? Delightful? Smart? Observant? So what does this mean, un mot? It can mean, well, a word. C’est quoi, le mot pour “moon?” What is the word for “moon?” Or, un mot can be a short discourse. We would call it a note.

Now if a French person wants to have a word with you, do you think they would ask for un mot? Absolutely not! What do you think they say in French if somebody wants to have a word with you? They will ask for two words, naturally. J’aimerais bien dire deux mots. This translates literally as, “I would like to say two words to you.” But the meaningful translation is, “I’d like to have a word with you.” We are on treacherous ground here, Dear Reader.

ONE SOUND

Before I disclose what the teacher had to say, I’d like to examine one sound, found, for example, in the word un cours. This word, which means a course at school, is pronounced, approximately, [coo] with a pause of breath at the end. Try it! Un cours, well done! Now the word cour, as in la cour de récréation, the playground, is pronounced the same way. This is also the same sound for the word “short” as in le temps est court, meaning time is short. Imagine that you are running after time like this: Je cours après le temps. Yet again, running is the same sound, [coo] with a pause at the end. Notice the sometimes “s” and the sometimes not. One last wrinkle in time: If your skirt is short, for example, since “skirt” has a feminine definite article, you say la jupe est courte. Now because it is feminine, you stick an “e” on the end of the adjective and then you get to pronounce the “t,” hooray! But remember that “time,” which, when it is short, ends with a “t” that you don’t pronounce.

TO GUESS OR NOT TO GUESS

Let’s start with you, Dear Reader. How are you going to know what ending to put on these words, all sounding like “cour”? What if I give you a dictation? (In a dictation I read a passage and you write it down.) We’ll start with English.

English: “In this French class, I run after time because time is short. I would very much like to go to the playground, but my skirt is too short to run.”

I believe we could write this down easily enough.

Now, imagine you are eight years old. You speak English at home. And now you have to cope with a dictée, a dictation in French. Your poor American brain hears all the different versions of the sound “cour,” in French: being in French class, running after time, and trying to get to the playground, but your skirt is too short. Here you go!

In French: « Dans ce cours de français, je cours après le temps, car le temps est court. J’aimerais bien aller à la cour de récré, mais ma jupe est trop courte pour courir. »

At eight years old, you are expected to master all this running around in French class. Can you come up with any strategies? French class, (cours) for example, ends in an “s” but is singular masculine. One person running around, (je cours) namely myself, also ends with an “s” although one person, namely myself, is singular. The playground is feminine, (la cour) as is my short skirt, (courte) although they end differently.

The eight-year-old has only one thing to say: Au secours! Help! (Don’t forget the “s” on yet another word with the “cour” sound.) The French teacher would say that the “t” in the short skirt is pronounced, so what is the problem? And the “ir” at the end of the verb “to run,” is quite distinct. The eight-year-old says, in the vernacular, “Yikes!”

MORASS

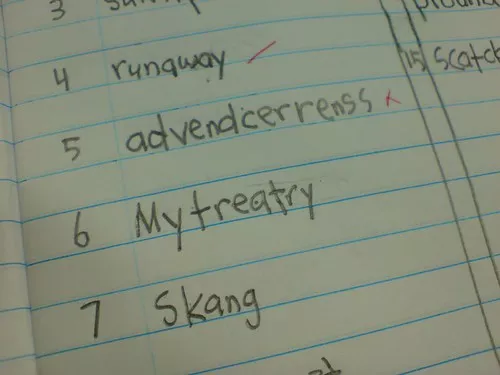

This is the morass of French spelling that a child in France is faced with. For every mistake, le or la confused or missing, for example, or an “s” present or lacking, and the student loses half a point. It is well within the realm of the possible to have a decidedly negative score on a dictation. Which brings me to le mot from my daughter’s teacher. The teacher wrote that my daughter’s handwriting was awful. I rose to the challenge and bought a fun book to practice forming letters, which my daughter resolutely refused to do. It was only years later that I learned that terrible handwriting was indeed her spelling strategy. The teacher was faced with deciphering whether there was a le or a la. Whether there was an “s” or not, a “t” or not.

MADAME LUNEL

I’d like to recommend Madame Luñel who taught in the fourth grade. She had the foresight to have the kids write in their carnet when a test was coming up, or a quiz, so they could plan their study time, helping them develop life-long study skills. ( She herself had to be exceptionally organized to pull that off.) I went to see her at the beginning of the school year, as I did every year starting when my daughter was 4, right up through 18. I explained to Mme Luñel that we were American, and that if there was anything we weren’t doing as parents that we needed to do, to please tell us. Madame Luñel turned to my daughter and said to her in French, “Why are you hiding your American parents?” My daughter smiled her lovely smile. I was especially pleased because that comment suggested to me that my daughter was doing just fine if no one suspected she had parents who, if I might say, were a bit clueless, especially at first, about how the system worked. Our ineptitude had not rubbed off on her!

At first our daughter was not especially forgiving with our shortcomings. We’d show up at the school gates when the place was locked up due to a French holiday. Or I’d send her to school in the prettiest shoes which turned out to be slippers. But her attitude softened when report cards went home. She told us how upset the parents of her classmates had gotten when the students got less than stellar grades. We just said, “You’re doing the best you can, honey.” When our daughter reported our reaction, her classmates looked at her with envy and admiration. Those American parents weren’t so bad, after all!

Here is a French language teacher with his pet peeves.

For those of you who speak a little French. Dos and don’ts up to date.

GODOT

Speaking of fooling the academic establishment, I just learned that Samuel Beckett engaged in deliberate maneuvering to do just that. He had returned to Trinity College in Dublin from a couple of years of teaching at the most prestigious Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris.

ASIDE

Don’t you find it paradoxical that a school could be at once normal and superior? Here it is in French: L’ENS est un établissement public à caractère scientifique, culturel et professionnel. I figure you can make this out because the Romance languages are Latinate.

BECKETT

Anyway, Uncle Wiki, an indubitable source, says this: “In 1930, Beckett returned to Trinity College as a lecturer. In November 1930, he presented a paper in French to the Modern Languages Society of Trinity on the Toulouse poet Jean du Chas, founder of a movement called le Concentrisme. It was a literary parody, for Beckett had in fact invented the poet and his movement that claimed to be “at odds with all that is clear and distinct in Descartes“.

Wait, what? Beckett made up a poet and a movement? And he gave a paper on it? I love his countering all that is clear and distinct in Descartes, leaving the rest intact! Descartes can be reduced for the purposes of this blog to opining, “I think, therefore I am.” Beckett was known to say that he didn’t like definitive statements, and eschewed what he thought, writing instead what he felt. A critic once said that the most important word in Beckett’s work was “perhaps.” Estragon and Vladimir, the two vagrants, are perhaps waiting for Godot, or perhaps waiting for someone to become Godot?