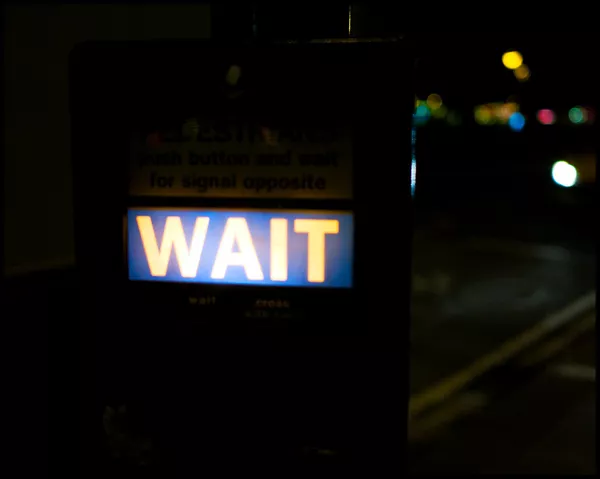

’ve been thinking about what it must be like to be waiting for Godot. What are we waiting for again?

’ve been thinking about what it must be like to be waiting for Godot. What are we waiting for again?

STORY

Today I was waiting in line for a woman to find her credit card at the grocery store. She asked the cashier to look at a different card, a debit card. “How much do I have on here?” she asked. He suggested she put it in the card reader to see. She went rummaging back in her purse. “Where is my card?” She said she could write a check. Ah, she found the card at last. You know what it’s like. You’ve got somewhere you have to be. You actually stride through the grocery store, only getting essentials in order to get out fast. And then the lady who can’t find her card.

Deep breath. It doesn’t matter. But it’s not natural. Waiting is not natural. Forward ho it is not.

ASIDE

The lady apologized and said she was a terrible person. She added that she was 96. Ninety-six years old and maneuvering with her cards and check book, and pushing out her grocery cart on her own two feet! Suddenly we were all waiting in that line to be 96 exactly like her.

WHY

One thing that gives weight to waiting is to remember what you are waiting for.

Our voyageurs, Didi and Gogo, from Samuel Beckett’s play, Waiting for Godot, remember meeting with Godot. They agree they made a vague prayer, a supplication. Godot, apparently, said he would see what he could do.

Towards the end of the first act, a young man appears, a boy, actually. His message is that Godot is not coming today after all. But he will come tomorrow.

The boy asks if there is any message. “Tell him you saw us,” Didi says. “You did see us?”

The boy replies that he did. That’s the message. “We were seen.” This moment gives me pause because these two gentlemen are on the margins of how we would look at their role in life. Profession, job even, family, hobbies—nothing to identify them, to place them. They were seen.

IS THAT ENOUGH?

My new friend, the French novelist and theoretician Milan Kundera, believes that modern writing reveals us to ourselves in the messy mundane. Is that our doom or our good fortune, he wonders.

What’s it like to be waiting and hopeful, and Godot does not come? Are we doomed or are we lucky to be waiting for someone or something important to us? Even asking that question is part of the beauty of the play. Let me quote a passage.

One of the men, Estragon, had a strange dream. Vladimir did not want to hear about it. Estragon says, “There are times I wonder if it would be better for us to part.” And then he reflects some more.

“That would be too bad, really too bad. (Pause.) Wouldn’t it, Didi, be really too bad?” (Pause.) “When you think of the beauty of the way.” (Pause.) And the goodness of the wayfarers.” (Pause. Wheedling.) “Wouldn’t it, Didi?”

We don’t often talk about the beauty in this play. But there it is.

ASIDE

I love the word “wheedling,” lest we all get too rapturous. There’s a Persian proverb that even in heaven there will be the occasional mosquito. Our ecstasy is tempered, but ecstasy it is. I was going to put an exclamation point but that would not show tempered beauty, right?

IN SHORT

What are you waiting for?

Definition 1) genuine question

Definition 2) get going!

They did not move.

Here’s a four minute instrumental piece called, “What are you waiting for? by Briovere Buffentis.

https://wordpress.org/openverse/audio/88945b94-63ea-42d4-af8a-fa647eb76bbf

loved this one!

Are there slower moving queues than in France where conversation (small talk)is not yet a lost art?… Great line when Didi asks, You did see us?.. the fate of the elderly, to not be seen.. until they hold you up at the supermarket.

I really enjoyed this post.

Thank you.

Best